By Larry Magid

Sextortion usually involves a perpetrator (typically male) getting hold of a picture of someone (typically female) and threatening to widely share those images unless the victim gives them something they want. And that something is often more images that are increasingly humiliating to the victim, but sometimes money.

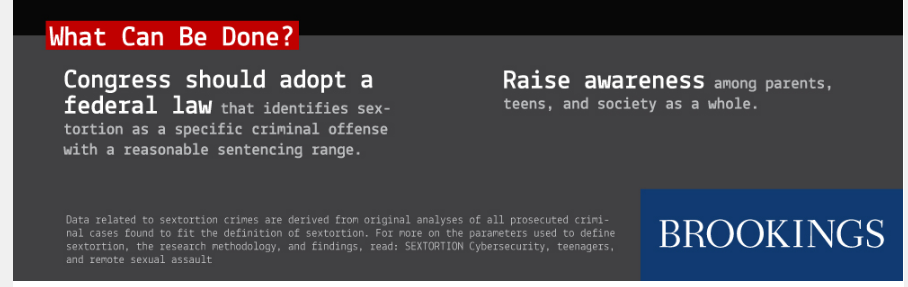

Brookings Institution fellow Benjamin Wittes looked at 78 prosecuted cases and found that many of them involved multiple victims — in some cases hundreds of victims. “Sextortion is a scalable offense,” said Wittes. “You can do a lot of it and some of these people manage to do it a whole lot before they get caught. Still, said Wittes, “we have no idea how much of it there really is but the number is much greater than we had thought before we started looking into the subject.” You can read the report here.

The report refers to the 78 prosecuted cases studied as “surely the tip of a very large iceberg,” but in response to my question, Wittes said that there is no data showing just how prevalent it is. “We have no idea. We know there are a bunch of cases and we know those cases account for a large number of victims.” He said that “to have a better sense of that we would need something like crime reporting data.” He said he wants to see government agencies that measure crime statistics start tracking sextortion.

Of the cases he examined, 88% involved victims under the age of 18. All of the adult victims were female and all of the perpetrators were male though he said that there were males among the child victims though there too most were female. Child pornography laws empower prosecutors in every state to seek harsh penalties against those who exploit minors, said Wittes, but this is not necessarily the case when the victim is over 18, he said.

Listen to Larry Magid’s 23 minute interview with study author Benjamin Wittes

How perpetrators get hold of images

There are several ways that perpetrators get hold of the images, said Wittes. Most common is “social media manipulation, in which the perpetrator tricks the victim into sending him the compromising pictures he then uses to extort more.” In some cases it’s a person she trusts who turns against her and in other cases, she is deceived into sending it to an imposter who appears to be her boyfriend but is really an imposter.

Another way is to hack into places where these images may be stored, presumably to share only with an intimate partner. Though less likely, a more insidious method is to hack into people’s webcams and take pictures of them when they think no one is looking. In the interview, Wittes calls upon technology companies to put hardware switches on devices to turn off the camera. “They what effectively amounts to a surveillance devices into the bedrooms of every technologically enabled person in the world.”

The victim impacts “are quite severe,” calling sextortion “remote sexual slavery,” he said “people think this is playful sexting but it’s not.”

More research needed

Wittes called sextortion an “understudied problem,” and I would agree. We know it exists but we don’t know how prevalent it is nor do we have a good idea of how the vast majority of victims are affected by it. We also don’t have data to know exactly how most victims respond and exactly why some comply with the perpetrator’s demand for more images and some, presumably, refuse to comply, perhaps taking the risk of having an image exposed rather than subjecting themselves to having even more images of them in the hands of the person sextorting them. These are important questions which need answers.

Scroll up to listen to interview with the author of this study