This post first appeared in the Mercury News

by Larry Magid

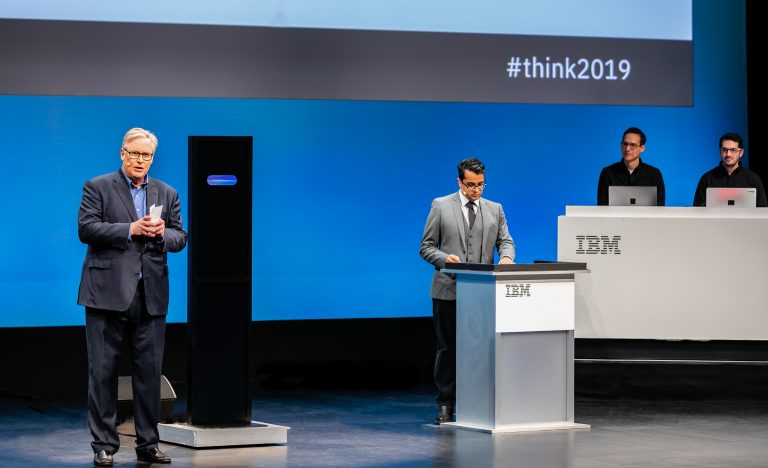

2016 World Debating Championships Grand Finalist and 2012 European Debate Champion Harish Natarajan was standing on the left side of the stage and a computer containing the software for IBM’s Project Debater was to his right. Also on-stage was the moderator John Donvan, host of Intelligence Squared who oversaw what may have been the first live debate between man and machine. The human won, but not by much. IBM Research’s Project Debater was a worthy opponent.

The debate which took place during IBM’s Think 2019 conference in San Francisco last week, proved that artificial intelligence has come a long way. The computer, which spoke with a female voice, didn’t just recite rote facts, but dynamically prepared arguments much like a human does during a debate.

I did pretty well when I was in the National Forensics League in high school and, based on what I saw from the YouTube video of this debate, the robot would have easily beaten me and just about any opponent other than a champion like Natarajan, who holds the record for most competition victories.

Neither the human nor the machine had much time to prepare. They were notified of the topic only 15 minutes before the debate began. And, just like two humans in a debate, both had to respond to the other. I expected Natarajan to do that brilliantly, but was a bit surprised and very impressed at how the machine was able to both understand Natarajan’s voice and respond to his arguments with rebuttals worthy of a good human debater.

During an on-stage chat after the debate, Natarajan admitted that the computer had a lot of knowledge and that its recitation of that knowledge was nicely phrased and contextualized.

Natarajan said that the real power of AI could be when human and machine work together: “If you take some of those skills and add a human being which can use it in slightly more subtle ways, I think that could be incredibly powerful.”

IBM scientist Noam Slonin said that “in terms of rhetorical skills,” Project Debater “is not at the level of a debater like Natarajan, but “the system is capable of pinpointing relevant evidence within a massive collection of data. The machine’s vocabulary is based on 10 billion sentences, which it uses to pinpoint little pieces of text that are relevant to the topic, argumentative in nature and hopefully support our side of the debate and then somehow glue them together into a meaningful narrative which is very very difficult for a machine to do.”

IBM Researcher Ranit Aharanov agreed with Natarajan’s assessment that combining the skills of machines and humans can be extremely powerful when it comes to organizing information “that’s digestible by humans in order to drive better decision making more quickly for humans.”

That human element that Aharanov talked about is the differentiator between what could become an incredibly helpful technology vs. the dreaded dystopian future where machines are making decisions for us. If it’s going to be a force for good, AI has to be there to serve humans, and humans have to remain in control.

That’s certainly the case with most of today’s limited AI functions such as the software behind Amazon Alexa or Google Home, which, for the most part, simply provides people with a limited amount of information such as the weather or the time it will likely take to get to work. Knowing the weather informs me of what to wear when I get dressed in the morning, but I’m making that decision, not Alexa. Some day Alexa might advise me of what I should wear, but I hope that she never dictates my wardrobe without at least giving me veto power.

I have a home security system that lets Alexa or Google Home unlock my doors or arm my alarm, but the system doesn’t allow me to use my voice to unlock a door or disarm the alarm because that could be dangerous if someone were to impersonate me or if the system simply malfunctioned. It would also be dangerous if the people programming the system had criminal intent and designed it to make it easier for people to rob me, which is where trust comes in. That’s certainly possible, but — right or wrong — I’m trusting that the companies I’m dealing with will never do that.

AI is also the driving force behind autonomous vehicles and even semi-autonomous ones like the so-called Autopilot software available for Teslas or even the adaptive cruise control in many cars that automatically slow you down or stop you, based on the speed of the car in front of you.

As I have said in previous columns, I now drive a Tesla Model 3 with autopilot, which, literally, makes life or death decisions for me as I’m using it to change lanes or transition from one freeway to another. I’m in control — sort of — but the software is paying attention to what it sees and senses and making split second decisions that I may or may not have the time to override. Because of this, I always look around before initiating a lane change (it changes lanes automatically but the driver has to approve it with the turn indicator). It would be easy to simply let the car make and implement those decisions, but, despite Tesla’s report of owners driving “over 1 billion miles using Autopilot,” and their assertion that “Tesla vehicles experienced 1 crash for every 3.34 million miles driven with Autopilot engaged, compared with the national average of “about 1 crash for every 436,000 miles,” I don’t want to be that 1 in 3.34 million.”

I got these stats from a report submitted to the California Department of Motor Vehicles. The DMV asked all companies testing autonomous vehicles to submit “Vehicle Disengagement Reports,” which are posted on a DMV webpage.

Those reports prompted the nonprofit group Consumer Watchdog to put out a press release saying that “Uber reported a whopping 70,165 interventions for only 26,899 autonomous miles tested, or 2.6 human interventions per mile driven.

Mercedes reported 1,194 interventions for only 1,749 miles tested or one intervention for every 1.46 miles driven.” Of course, not all human interventions represent a failure of these systems but they are a reminder that — at least during this testing period — it’s important for humans to remain in control.

But I would argue that it will always be essential for humans to be in control not only of autonomous vehicles, but of all forms of AI including smart machines like IBM’s Project Debater that are capable of reasoning, arguing and even decision making. It’s one thing to let a car take you from place to place by itself or have a machine recommend a course of action but, ultimately, we need to make sure that humans are setting the course, even if we’re not in the driver’s seat.