Modern cell phones know where you are. This can be a very good thing, but — in the wrong hands — it can also lead to potential abuse.

As Kaofeng Lee and Erica Olsen point out in the article, Cell Phone Location, Privacy and Intimate Partner Violence from the website of the National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV):

Sharing one’s location can be quite dangerous, however, when a stalker or abuser uses this information to stalk, harass, and threaten. For victims of domestic violence, assault or stalking, knowing how much information may be inadvertently shared about them is key to planning for privacy and safety.

NNEDV has more advice at Cell Phone & Location Safety Strategies

Fortunately, there are ways to control your phone’s location features. I’ll get to specifics for iPhones and Android phones later in this article but if you believe you are in danger, NNEDV recommends that you call 911, a local hotline, or the U.S. National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 and TTY 1-800-787-3224.

Location for first responders

Although there are now plenty of commercial uses for location-aware devices, they were first put there — and required by the federal government — so that first responders could find you in an emergency. If you dial 911 from a landline, the operator knows exactly where you are because they can trace that phone’s location. That didn’t used to be the case for cell phones but now 911 operators have access to geolocation data from GPS satellites, Wi-Fi hotspots, Bluetooth signals and cellular networks.

Lots of location apps

But now that data can also be used for navigation, commercial purposes and a wide variety of apps, including some designed specifically to share your location with others. There are “phone finder” apps that allow you (or anyone who knows your Apple or Google ID and password) to track your phone. There are apps designed to share your location with friends or family and there are apps like Yelp, Facebook and Foursquare designed to share your location with the app developer and — depending on how you use them — your friends on those services. Even photos you take with your smart phone (or a regular digital camera) can record your location and disclose it to those you share the photos with.

Turning off location (almost) completely

The good news is that (with the exception of e-911), you can turn off location completely or limit what apps have access to that location. Here’s how to turn it off (almost) completely:

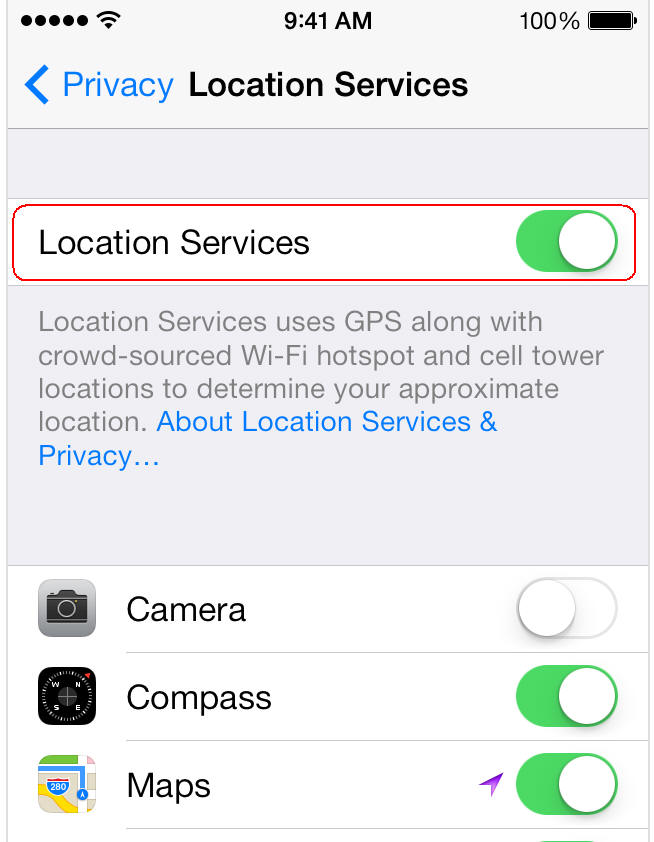

iPhone or other iOS device:

This advice applies to iOS 7. Here’s an Apple help page that covers other versions

1. Go to Settings > Privacy > Location Services

2. Turn location services off by touching or swiping the Location Services slider. You can also turn off location awareness of specific apps by touching or swiping their slider just below the general location setting.

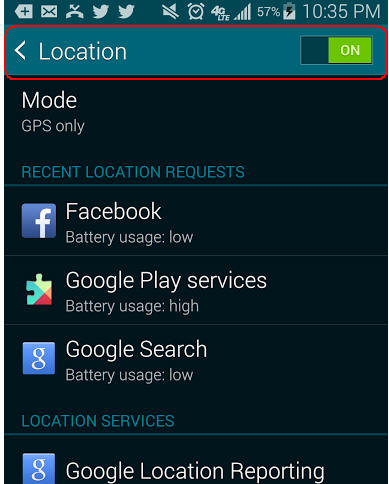

Location settings can be slightly different on different Android devices but in general:

Go to Settings and scroll down until you see Location. In some cases you need to first select General and then Location.

Controlling location history and what apps have access

You may want to use location for some purposes, such as navigation, but turn it off for other apps.

On an iPhone just below where you turn location on or off completely, you’ll find a list of apps that may be location aware. Simply turn off location for any apps that you don’t want to be able to access that information.

On an Android phone you can sometimes control location awareness from individual app’s menus. If not, consider deleting the app or turning off location in general.

Google also stores location history but you can turn that off or delete what’s been collected.

- Open Google Settings from your device’s apps menu:

- Devices running Android 4.3 or lower: Touch Location > Location History.

- Devices running Android 4.4: Touch Account History > Google Location History > Location History.

- Touch Delete Location History at the bottom of the screen.

- Read the dialog box that appears, check the box next to “I understand and want to delete,” and touch Delete.

(Source: Google location help page)

You can also delete specific location history by logging into your Google account and going to Google’s Location History website. From there you can delete individual locations, locations by date, or your entire location history.

Cell phone accounts and ‘family plans’

Also, be aware that if the phone is in your abuser’s name or in a family plan where that person has access, they may be able to access your phone records and other data from the phone company’s website. There could even e a phone-company locator service that the person can use to find your phone. NNEDV recommends abuse survivors have their own account.

At NNEDV’s 2014 technology summit, Longmount Police Depoartment Detective Bryan Franke suggested that if you change phones to get rid of one infected with spyware, be careful about restoring or transferring all of the old phone’s apps and data to make sure the new phone doesn’t just replicate the old one.

Other considerations

Be aware that anyone who has physical access to your device can change the settings, so be careful who has access and check the settings periodically if you have reason to worry. Also, be careful about the apps that you install and how you use them. Look at the permissions that they ask for (especially location) and if you do install an app that can disclose your location, be careful how you use it. Something as innocuous as recommending a restaurant you’ve visited could get you in trouble. Kaofeng Lee & Erica Olsen recommend that domestic violence survivors “put a lock code on the phone” to make it harder for an abuser to modify your settings and they further warn survivors to “be careful not to install programs that are unknown, especially if the suggested app is from the abuser or mutual friends. Survivors should also make sure that family and friends do not download apps onto their phone without knowing about it or knowing what the app does.”

Parents can get mobile phone advice from A Parents’ Guide to Mobile Phones from ConnectSafely.org (the non-profit Internet safety organization where I serve as co-director).

This post first appeared on Forbes.com