This post first appeared in the San Jose Mercury News

by Larry Magid

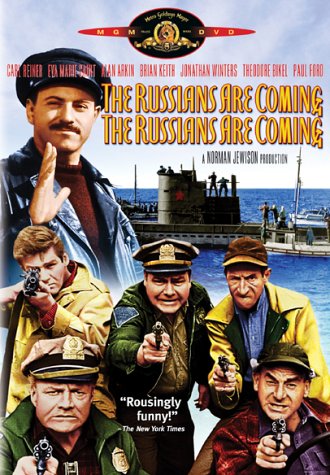

I grew up during the Cold War and, like most people at the time, was conditioned to fear the Soviet Union, which many people simply referred to as “Russia,” even though it included several other Soviet republics. Worry was so strong that the title of a popular 1966 comedy film said it twice: “The Russians are Coming, the Russians are Coming.”

Well, the Soviet Union is no more, but our concern about Russia remains strong. Not only are people talking about Russia’s meddling in Ukraine and possible involvement with the shooting down of a Malaysian jetliner there; they’re also talking about Russian hackers and cyber criminals like the ones who, according to news reports last week, stole 1.2 billion passwords and user names.

What’s particularly interesting about this story is how the thieves used a series of techniques to amass the data. According to Hold Security, which uncovered the breach, “the gang acquired databases of stolen credentials from fellow hackers on the black market,” and then used that data “to attack email providers, social media and other websites to distribute spam to victims and install malicious redirections on legitimate systems.”

Then, according to Hold, they altered their approach to get access to data from botnet or “zombie networks” of computers owned by innocent people whose machines were infected and enlisted for this purpose. The botnets were used to identify vulnerabilities on websites people visited, and that yielded a treasure trove of data from more than 400,000 websites large and small. It’s a criminal version of “big data.” The more information you have access to, the more you’re able to infer based on what you already know.

In other words, like the Russian experts who challenged the U.S. during the Cold War, these data thieves are extremely sophisticated and multifaceted, willing to use a variety of different strategies to achieve their ends. But instead of promoting an ideology, they’re seeking financial gain.

Last week’s story was just the latest of many reports about hackers operating from Russia or other former Soviet republics. Last year, for example, it was disclosed that five Russians and a Ukrainian, over a period of seven years, were able to steal more than 160 million credit and debit card numbers, according to the U.S. Justice Department. “This type of crime is the cutting edge,” said U.S. Attorney Paul J. Fishman. “Those who have the expertise and the inclination to break into our computer networks threaten our economic well-being, our privacy, and our national security.”

It reminds me of that 1966 movie, but instead of hapless Russian sailors arriving at the New England coast in a submarine, the Russians invading us now never need to leave the motherland. Because the Internet has made it possible for cyber criminals to enter your living room without having to physical step on American soil, perhaps it’s time for a new movie titled “The Russians Are Here, the Russians are Here.”

Depending on what report you look at, Russia is almost always among the top four cyberthreats. U.S. government officials worry a lot about state-sanctioned cyber-espionage coming from China, and other countries worry about cyberattacks from the United States, both because of government spying and the fact that many U.S. computers have been infected with malware and recruited into botnets. Even if the hacks are orchestrated elsewhere, the actual attacks may come from U.S.-based systems.

“American machines can serve to disseminate it, but the command and control is in Russia and Eastern Europe,” according to Tom Kellermann, Trend Micro’s chief privacy and security officer.

In an interview, Kellermann listed some reasons that the Russians are so good at hacking. Chess is the national pastime and many Russians are strategically savvy. And when the United States won the Cold War, “we dropped the religion of capitalism,” including to folks who had been trained by computer scientists from the Soviet intelligence community. The third reason, said Kellermann, is “an unspoken agreement” between the hackers and the regimes that “you never target a corporation or government agency in your own country and if you find something interesting, you will share it with the government.”

Kellermann said that the Russians are the world’s best hackers, but he also has respect for the hacking talent in other former Soviet republics. “You have to pay your respects to the adversary here that’s playing chess with us.”

Of course, there are plenty of tech-savvy Russians doing productive, beneficial work including those who work for Moscow-based Kaspersky Lab and other Russian security companies. I’ve been to Russia and have met with some of these security professionals and, even though they are paid for their work, they are motivated to do the right thing. Which reminds me of the title of yet another 1960’s movie: “From Russia with Love.”