(This post is adapted from Larry’s Daily News column of July 18, 2012)

by Larry Magid

Like other engineers at Facebook, Arturo Bejar, a mathematician by training, is helping to build new products to encourage users to communicate and share.

But his products are a bit different. He works on social tools to help people get along with each other and resolve conflicts ranging from the posting of annoying pictures to serious cases of bullying.

Listen to Podcast interview with Facebook Engineering Director Arturo Bejar about social reporting tools and compassion research

Working with researchers from Yale, Berkeley and Columbia University, Bejar and his team are tasked with improving the tools that enable Facebook users to report and resolve problems. When analyzing user abuse reports, Bejar and the researchers noticed that many complaints did not fall under the company’s Community Standards, which are the rules of the road that Facebook requires users to follow. These rules cover offenses like violence and threats, encouragement of self-harm, bullying and harassment, hate speech, nudity and pornography and such things as spam and phishing scams. Violation of these terms can result in content being taken down and – in some cases – being kicked off the service.

And while Facebook has staff around the world who deal with reports of serious abuses, they also hear about issues that have more to do with interpersonal relationships among members — like someone posting or tagging you in a photo that you don’t like, or someone saying something unpleasant about you that – while annoying – is not considered bullying or harassment.

“We found when we were looking at reports that there were a lot of things getting reported that were really misunderstandings or disagreements among people who use the site,” said Bejar in a recorded interview.

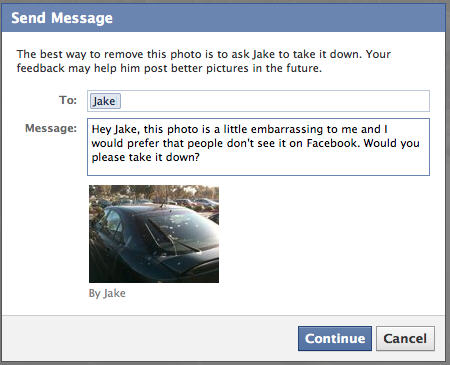

So, instead of putting Facebook employees in the impossible position of resolving feuds, the company started experimenting with “social reporting” designed to encourage users to work out issues between themselves or seek help from trusted friends or relatives. For example, if you see a photo on Facebook that bothers you, you can click the Options link and “Report This Photo.” But rather than automatically report to Facebook, it asks you “Why are you reporting this photo,” with choices ranging from “I don’t want others to see me in this photo” to “this photo is harassing someone.” If it’s just something you don’t like you can specify why it bothers you (such as “it makes me sad” or “it’s embarrassing”) and you’ll be able to send a message with suggested wording like “Hey Marie, seeing this photo makes me a little sad and I don’t want others to see it. Would you please take it down?”

If it’s an issue that can’t be easily resolved, Facebook lets you seek help from a trusted third party or, if you feel you need big guns, you can still seek help from Facebook support staff who will intervene if the photo or post violates community standards.

Bejar said that most of the reports they hear about have to do with unintentional slights like posting an unflattering picture of someone. What they found is that if they simply put up a blank message box for asking a friend to take down a picture, only 20% of the people will fill out the dialog box to send a message to a friend. “Asking your friend to take a photo down that they uploaded is actually kind of difficult.” They began experimenting with various default messages to “trigger a compassionate response” and then studied how people responded to those options.

Based on this research, they are fine-tuning their social reporting and in the process of rolling out new suggested messaging that is proving to be more effective.

Some of this research was presented to the public earlier this month when Facebook conducted its second “Compassion Research Day” at its Menlo Park headquarters. In addition to Bejar and others at Facebook, speakers included Marc Brackett from Yale’s Health, Emotion, & Behavior Laboratory, Robin Stern of Columbia University, Dacher Keltner, Director of Berkeley’s Social Interaction Laboratory and Piercarlo Valdesolo of Claremont McKenna College.

Bejar said that his work enjoys “extraordinary support” from CEO Mark Zuckerberg and Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg who see it as “a big part of our mission and what it means to support the people who use Facebook.”

A parent of a young son, Bejar is both optimistic and realistic. He doesn’t necessarily think that being a kid is better or worse than it used to be but it’s going to be a “different world.” He added, “when I look at my son and the access he has to computers, how he is learning to program at this age and how he uses the different services that connect him online, I think he’s going to have a wonderful childhood and it’s going to be a wonderful set of teenage years.” But, said Bejar, “I also think that there will be significant challenges as he becomes a teenager.”

Truer words were never spoken.

Disclosure: Larry Magid is co-director of ConnectSafely.org, a non-profit Internet safety organization that receives financial support from Facebook

Be the first to comment