I’ve been covering technology since the early eighties and, for the first twenty years or so of my career, I recall seeing very few negative media stories and even fewer complaints from politicians. For much of that time tech pretty much got a free ride. Journalists and elected officials were in awe of what Apple, Microsoft, Yahoo and other tech companies had accomplish and were optimistic about what the future might be.

There were some anti-trust hearings and an eventual trial over Microsoft’s domination of personal computing and the fear that would carry over to the internet. But for the most part, politicians were either ignorant or positive when it came to tech. The word “big tech” was not a major part of our vocabulary.

Fast forward to 2019 when politicians from both sides of the aisle seem almost obsessed with potential problems arising from tech companies. The President and his allies claim that Twitter, Google and Facebook are biased against conservatives while Democrats complain about how these platforms were illegitimately used by Russia to tilt the 2016 election in favor of Donald Trump. Both sides complain about privacy and there are people across the political spectrum who agree on that tech needs to be regulated, even if they can’t agree on hardly anything else.

Tech was very much on the agenda at Tuesday night’s Democratic debate as candidates responded to questions from New York Times national editor Marc Lacey as well as each other.

Lacey began by asking Andrew Yang if he agreed with Senator Elizabeth Warren’s call to break up companies like Facebook, Amazon and Google. Yang agreed that “Senator Warren is 100 percent right in diagnosing the problem,” but diverged on solutions, pointing out that “we also have to be realistic that competition doesn’t solve all the problems. It’s not like any of us wants to use the fourth best navigation app. That would be like cruel and unusual punishment. There is a reason why no one is using Bing today.” He went on to say “it’s not like breaking up these big tech companies will revive Main Street businesses around the country” and “Breaking up the tech companies does nothing to make our kids healthier,” after claiming that “Studies clearly show that we’re seeing record levels of anxiety and depression coincident with smartphone adoption and social media use.”

Warren retorted that competition isn’t working. “About 8 percent, 9 percent of all retail sales happen at bricks and sticks stores, happen at Walmart. About 49 percent of all sales online happen in one place: that’s Amazon,” she said. I fact-checked her numbers, and she’s not far off. Warren added, “It collects information from every little business, and then Amazon does something else. It runs the platform, gets all the information, and then goes into competition with those little businesses.”

Tom Steyer agreed that tech companies “either have to be broken up or regulated,” but then turned his attention to why he could beat President Trump — a useful pitch for Democratic voters, but not very helpful when it came to the key question.

Corey Booker said “we have a massive crisis in our democracy with the way these tech companies are being used, not just in terms of anti-competitive practices, but also to undermine our democracy,” adding “we need regulation and reform.”

I agree with Beto O’Rorke’s first comment that “we need to set very tough, very clear, transparent rules of the road,” but not with his assertion that tech companies like Facebook are “more akin to a publisher. They curate the content that we see.”

While it is true that algorithms used by Facebook and other social media companies help surface what people see, the content itself is generated from users, not from journalists or other professionals work who for and report to the companies. The problem with O’Rourke’s claim is that classifying social media companies as publishers means they are responsible for everything on their platform, which could have a chilling effect on the free speech of their users. The only way Facebook could vet and verify everything anyone posted would be to hire thousands of editors to read every post and decide whether it was a valid opinion or a true fact, just as newspapers do for everything from reporter generated stories to op-eds. Even letters to the editors go through an editing process before they’re printed in most newspapers, which holds them to different standards than what people can post on online forums or social media. That’s not to say they shouldn’t posts that violate their terms of service, but making that a requirement could have unintended consequences.

Kamala Harris, used the tech question to take a shot at Elizabeth Warren, asking her to back her demand that “Twitter suspend Donald Trump’s account.” Warren, who is taking a lot more incoming now that she’s one of the top contenders, wouldn’t take the bait and I don’t blame her. While it’s very true that Donald Trump has used Twitter to make mean comments and spread false information, it’s also true that — whether you like him or not — he’s President of the United States and what he says is — for that reason alone — is news worthy. There are lines that even public officials shouldn’t cross, but it’s right for Twitter to give him and other politicians a platform and to continue to give any other Twitter user the right to comment, respond and express their reaction to what the President posts.

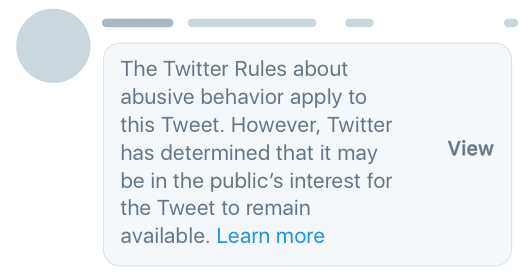

In June, Twitter announced a policy to “place a notice – a screen you have to click or tap through before you see the Tweet – to provide additional context and clarity,” whenever a public official posts a Tweet that “would otherwise be in violation of our rules.”

Although I’ve expressed my thoughts on what was said Tuesday night, I’m not taking sides in the primary or the election, but — along with many in Silicon Valley and across the country — I will be watching to see how the candidates grapple with the very real issues of how tech is affecting our lives, our economy and our democracy.