Macintosh Shapes Up a Winner

by Lawrence J. Magid

The Los Angeles Times

January 29, 1984

I rarely get excited over a new computer. But Apple’s Macintosh, officially introduced last Tuesday, has started a fever in Silicon Valley that’s hard not to catch. My symptoms started when I talked with some devotees from Apple and the various companies that produce software, hardware and literature to enhance the new computer. By the time I got my hands on the little computer and its omni-present mouse, I was hooked. Apple has a winner.

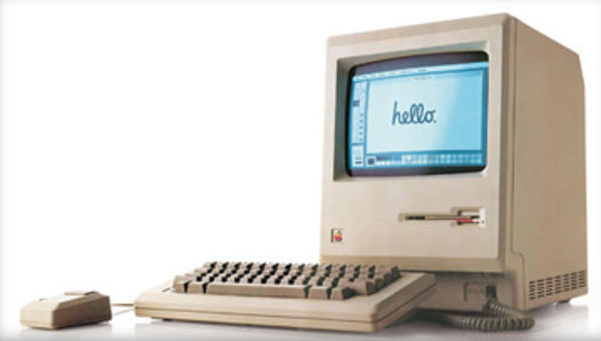

The Mac, which retails for $2,495 is about 14 inches tall and takes up about the same amount of desk space as a piece of 8 1/2 x 11 paper. It is smaller and lighter than most of the so called “portable” machines. The entire system can be slipped into an optional ($99) padded carrying case to be hoisted over your shoulder or placed under an airline seat. The case and computer together weigh 22 pounds.

Of course any computer’s real value is based on what you can do with it. For the first 100 days, Apple is including two valuable programs, MacPaint and MacWrite free with the machine. MacWrite has most basic word processing features with one outstanding addition. It can vary the size and style of your type on the screen and on paper, when used with Apple’s new $495 Image Writer printer. This computer/printer/software combination produces the first truly “what you see is what you get” word processing system on a moderately priced microcomputer. You can vary the type size from 9 point (about the size used in most newspapers) to 72 point headlines. You can also change your type style, selecting an Old English font or one of the more common type styles. Your type can be in bold, italic, underline or even shadow print. All this magic is controlled by the computer itself–the software merely takes advantage of it.

Write and Illustrate Reports

MacPaint is to graphic images what MacWrite is to words. I’m no Picasso, but I found myself drawing some rather pleasing images, using the mouse as a paint brush to draw pictures on the screen. You can paint with different size strokes (“brushes”), in patterns or using pre-designed shapes. It’s easy to custom design a letterhead, a map to your house, or even a self-portrait. The images you create in MacPaint can be integrated into documents produced on MacWrite, so you can create your own illustrated reports.

Until 1981, Apple, with some competition from Radio Shack, dominated the personal computer industry with its Apple II. The current version of that machine is still very popular. Apple started to loose market in 1981 when IBM introduced the first popular 16 bit computer. The IBM PC soon became an industry standard. Meanwhile the Apple Apple III was an unqualified dud and sales for its 32 bit Lisa were disappointing. Some analysists thought that Apple was a dying company. Apple’s young Chairman, Steve Jobs blames his company’s relatively poor performance on trying to compete with IBM on its own terms rather than “getting back to our roots.” With former Pepsi president John Sculley at the helm, Apple is now focusing its marketing efforts on small businesses, home users, and colleges rather than Fortune 500 companies.

The Macintosh is as innovative today as the Apple II was in 1977. It’s one of the few computers introduced in the last 18 months that makes no attempt to imitate the IBM PC.

It does, however, draw on Apple’s experience with the larger and more expensive Lisa. Like the Lisa, it uses a hand-held “mouse”–a small pointing device which enables the user to select programs, and move data from one part of the screen to another. Also like the Lisa, Macintosh uses a black and white display screen whose resolution is so high that it can quickly draw detailed pictures while at the same time display crisp and readable text. Apple did more than scale down the Lisa. To the contrary, the Macintosh team came up with so many innovations that Apple decided to re-design the Lisa so it too can run Macintosh software. Apple has also introduced three new higher performance Lisa computers with prices starting at $3,495. The Lisa sold for about $10,000 when it was made available last spring.

It’s Easy to Learn

The main advantage of the Macintosh is that it’s very easy to learn and use. Apple claims that novices can learn to use the Mac in as little as 30 minutes. The company is banking on the machine’s simplicity and modest price to attract “millions” of users over the next few years.

The main advantage of the Macintosh is that it’s very easy to learn and use. Apple claims that novices can learn to use the Mac in as little as 30 minutes. The company is banking on the machine’s simplicity and modest price to attract “millions” of users over the next few years.

The system comes in three pieces. The main unit houses the 9-inch screen, a built-in disk drive and all the machine’s circuits and connectors. The separate keyboard is attached to the unit via what looks like a modular telephone cord. The mouse, too, has its own cord and connector.

The system is driven by a 32 bit Motorola 68000 central processing unit. It comes with 128K of Random Access Memory (RAM), 64K of Read Only Memory (ROM) and one 400K disk drive. The 32 bit CPU and the extensive ROM are largely responsibile for its impressive graphics capability. The machine will eventually be upgradable to 512K once the new breed of 256K RAM chips become commercially available. An optional second (external) disk drive is $495.

Instead of using the 5 1/4 inch floppy disks that the Apple II helped standardize, the Mac uses 3 1/2 inch mini-floppies. These disks come with a built-in protective cover, can fit in a shirt pocket, and are far less vulnerable to damage than standard floppies. Apple will also be using the 3 1/2 inch disks on its new Lisa series.

Once you’ve set up your machine, you insert the main system disk, turn on the power, and in a minute you are presented with the introductory screen. Apple calls it your “desk top”. What you see on your screen looks a lot like what you might find on a desk. Instead of just a blinking cursor you see pictures, called icons, that graphically represent the things you can do with the computer. One of them is a picture of a hand, writing on a piece of paper. That represents the MacWrite word processing program. Another shows a hand drawing on paper to represent the MacPaint graphics program. Other options are represented by equally clever icons. Any files that you have created are also graphically depicted on your electronic “desk top.”

To select a program, you move the mouse to the icon and press the button on the top of the little rodent. If there are any additional options, they are displayed at the top of the screen, so you can move the mouse to make the appropriate selection. When this process was described to me, it sounded cumbersome, especially since I’m already comfortable with using a keyboard. But the mouse is so much more intuitive. As infants we learned to move objects around our play pens. Using a mouse is an extension of that skill.

All the commands are presented and issued in the same manner. Apple has gone to great length to insure that all of its software uses the same interface. What’s more, they are using their extensive influence to assure that independent software vendors follow the lead. The intelligence that operates the mouse and creates the graphic icons is built into the machine’s ROM — making it relatively easy for software manufacturers to adhere to Apple’s standards.

The value of a standard user interface can’t be overstated. I run dozens of programs on my computer, and each software company has its own idea of how to move the cursor, erase data and save files. Even an experienced user must take frequent peaks at the programs’ help menus and reference cards. If Apple gets its way, every program you buy will use the same basic set of commands. Microsoft Corp, in Bellvue, Washington, has announced Mac versions of its popular Multiplan spreadsheet program, BASIC language, and Microsoft Word–an innovative new word processing package. Lotus Development Corporation (Cambridge, MA) has has a forthcoming Mac version of its best selling 1-2-3 integrated spreadsheet, and Software Publishing Company (Mountain View, Calif) will release its PFS series of data base management tools. Apple provided pre-release versions of the Mac to these and more than 100 other software companies so that their products could be available soon after the release of the new machine.

Available software is critical to the success of any new computer system and Apple is counting on broad support since the machine can’t run software written for MS-DOS or any other standard operating system. The machine’s inability to run MS-DOS could be its salvation or its downfall.

Machine specific magazines help spread the excitement of a new computer. PC World Communications, Inc. (San Francisco) has already released the first issue of Macworld, an attractive and well written user magazine. The 145 page premier issue includes a photo essay on the Mac’s hardware, several software reviews, tips for using the new machine, and a behind the scenes series of profiles on the people responsible for “Making the Macintosh.” Within a few months there will be other magazines and scores of books about the new computer. Whether Apple can take a byte of out IBM’s sales remains to be seen. But the new Macintosh has gotten off to a delicious start.