by Larry Magid

In 1973, the delegates to the official Paris Peace Talks to end the war in Vietnam came to an agreement, but, by the time hostilities came to an end, more than a million people had died. What many people don’t know is that students from those same countries came to an agreement two years and tens of thousands of deaths earlier. This is the story of the “People’s Peace Treaty” from my perch as one of people who helped it along.

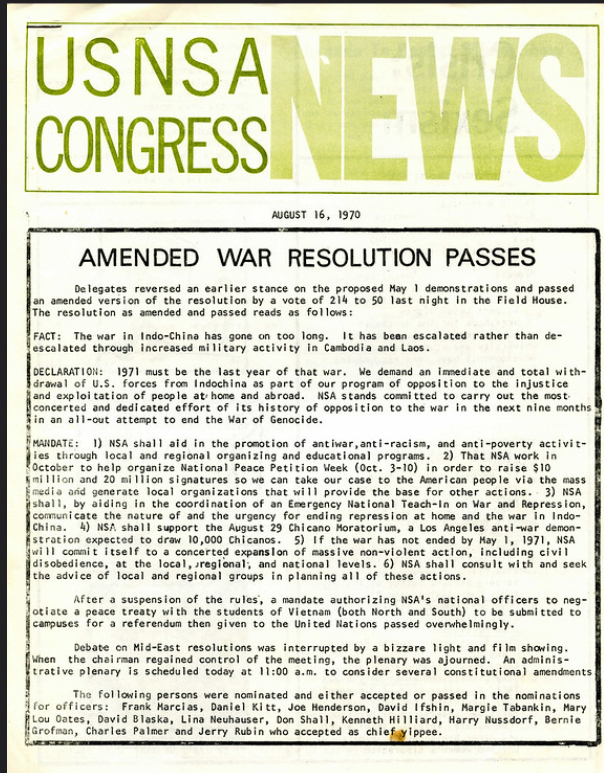

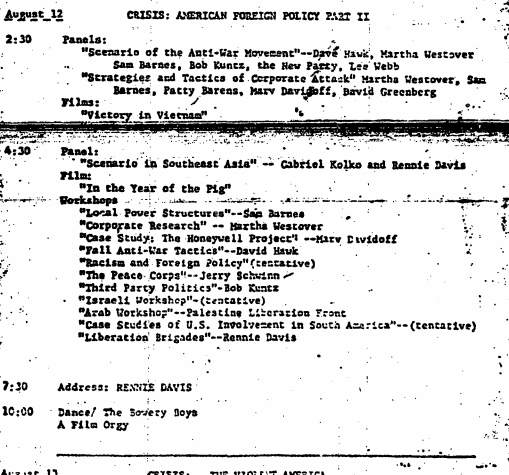

In August, 1970, the United States National Student Association (NSA) held its annual National Student Congress at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota. I was there as the director of NSA’s Center for Educational Reform but, from an historical perspective, the most important event at that Congress was the overwhelming passage of a resolution calling for the organization’s officers to “negotiate a peace treaty with the students of Vietnam (North and South) to be given to campuses for a referendum and then given to the United Nations.” The Student Congress also approved a series of other antiwar activities and pledged that if the war weren’t over by May 1970, support for “massive nonviolent action, including civil disobedience. Here is a brief prelude on NSA’s support of the treaty.

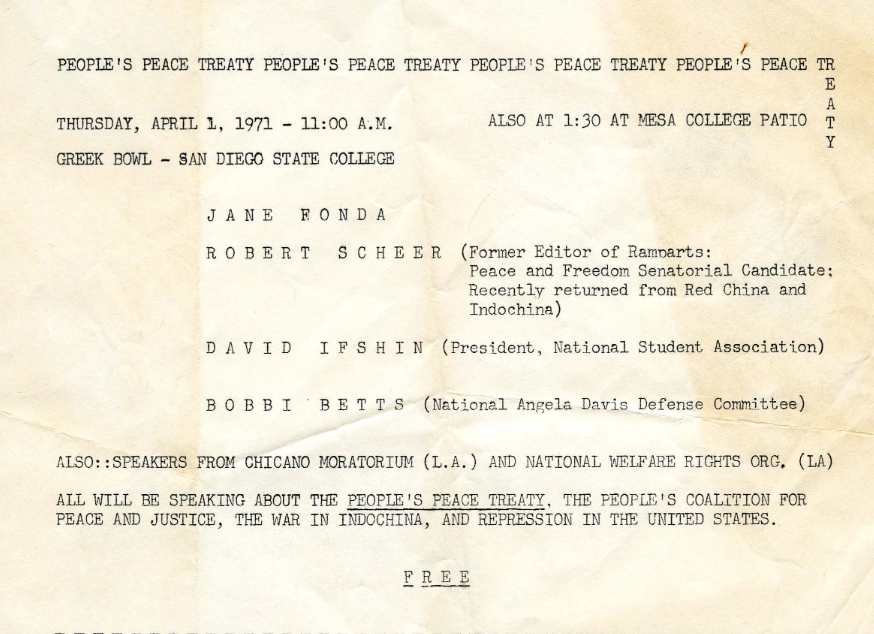

That student congress also elected David Ifshin as President of NSA who led the U.S. delegation in December of that year. Student leaders from both South and North Vietnam were also onboard. Charlie Palmer, who was outgoing president of NSA during the student congress, had earlier visited student leaders in South Vietnam on a fact-finding mission.

Shortly after he took office, Ifshin, who died in 1996 at 47, asked me to assist in what would be known as “The People’s Peace Treaty” (PPT).

Rennie Davis letter & Paris meeting

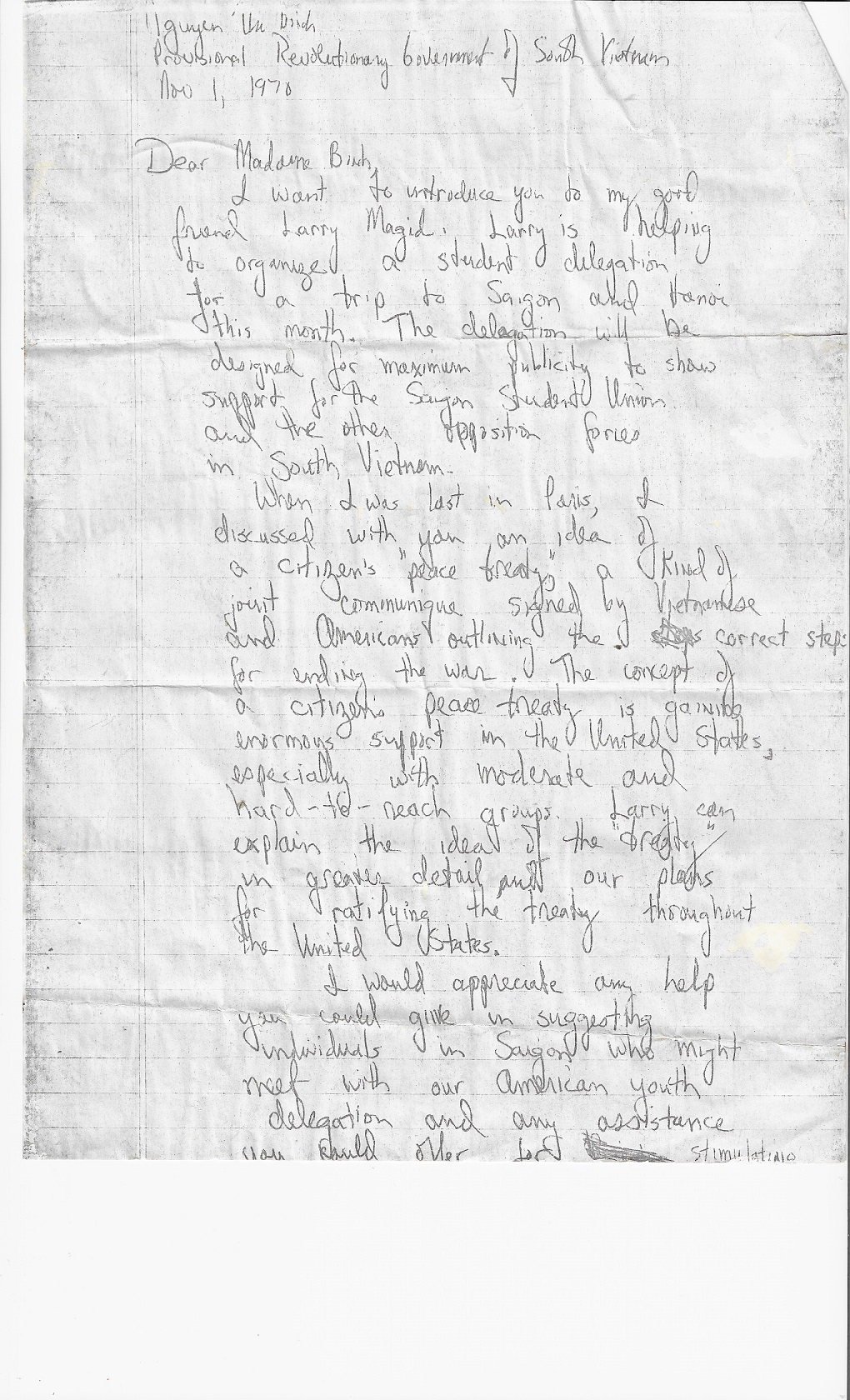

On November 1, 1970 I flew from Washington to Paris on the first leg of a trip that also took me to Algiers and London. I arrived at the Air France departure lounge at Dulles Airport early so I could meet with antiwar activist and Chicago 7 defendant, Rennie Davis who I sat with as he hand-wrote a letter of introduction to Madame Nguyễn Thị Bình, foreign minister of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam (AKA National Liberation Front or “Viet Cong”) who would later sign the 1973 official Paris Peace Accords. I had hoped to meet with all the delegations of the Paris peace talks, including the U.S., but was only able to get an appointment with Binh’s delegation.

Davis’s letter read in part, “When I was last in Paris, I discussed with you an idea of a citizen’s ‘peace treaty,’ a kind of joint communique signed by Vietnamese and Americans outlining the correct steps for ending the war. The concept of a citizen’s peace treaty is gaining enormous support in the United States, especially with moderate and hard-to reach groups. Larry can explain the idea of the “treaty” in greater detail and our plans for ratifying the treaty throughout the United States.” Here’s the full text of the letter:

Nguyễn Thị Bình

Provisional Revolutionary government of South VietnamNovember 1, 1970

Dear Madame Binh,

I want to introduce you to my good friend Larry Magid. Larry is helping to organize a student delegation for a trip to Saigon and Hanoi this month. The delegation will be designed for maximum publicity to show support for the Saigon Student Union and the other opposition forces in South Vietnam.

When I was last in Paris, I discussed with you an idea of a citizen’s “peace treaty,” a kind of joint communique signed by Vietnamese and Americans outlining the correct steps for ending the war. The concept of a citizen’s peace treaty is gaining enormous support in the United States, especially with moderate and hard-to reach groups. Larry can explain the idea of the “treaty” in greater detail and our plans for ratifying the treaty throughout the United States.

I would appreciate any help you could give in suggesting individuals in Saigon who might meet with our American youth delegation and any assistance you could offer for ….. (that’s the end of page one — page two is missing”

Rennie Davis (click for image in Rennie’s handwriting)

Meetings with Madame Binh, Eldridge Cleaver and British antiwar activists

After handing her Rennie’s letter I had a good discussion with Madame Binh. I was struck that one of the top leaders of the often vilified so-called “Viet Cong” was a kind and gentle woman who went out of her way not only to ask me about the peace movement in the United States, but my own life and family.

After leaving Paris, I travelled to Algiers where I discussed the treaty with Black Panther leader in exile Eldridge Cleaver, Kathleen Cleaver and their guest, Dr. Timothy Leary, who was also living in Algiers in exile. My next stop was London to drum up support for the treaty with leaders of Britain’s antiwar movement. The Black Panther Party had aligned itself with the U.S. antiwar movement and the antiwar movement in the U.K. was vibrant and influential.

Rennie Davis, who died on February 2, 2021, was instrumental in drafting and promoting the PPT both in the United States and around the world.

Delegation to Hanoi and Saigon

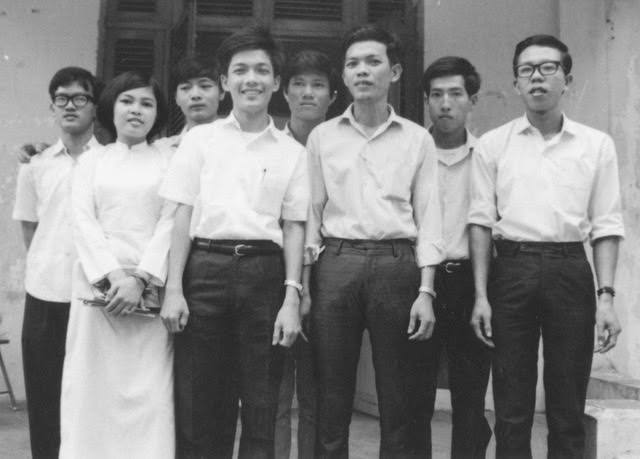

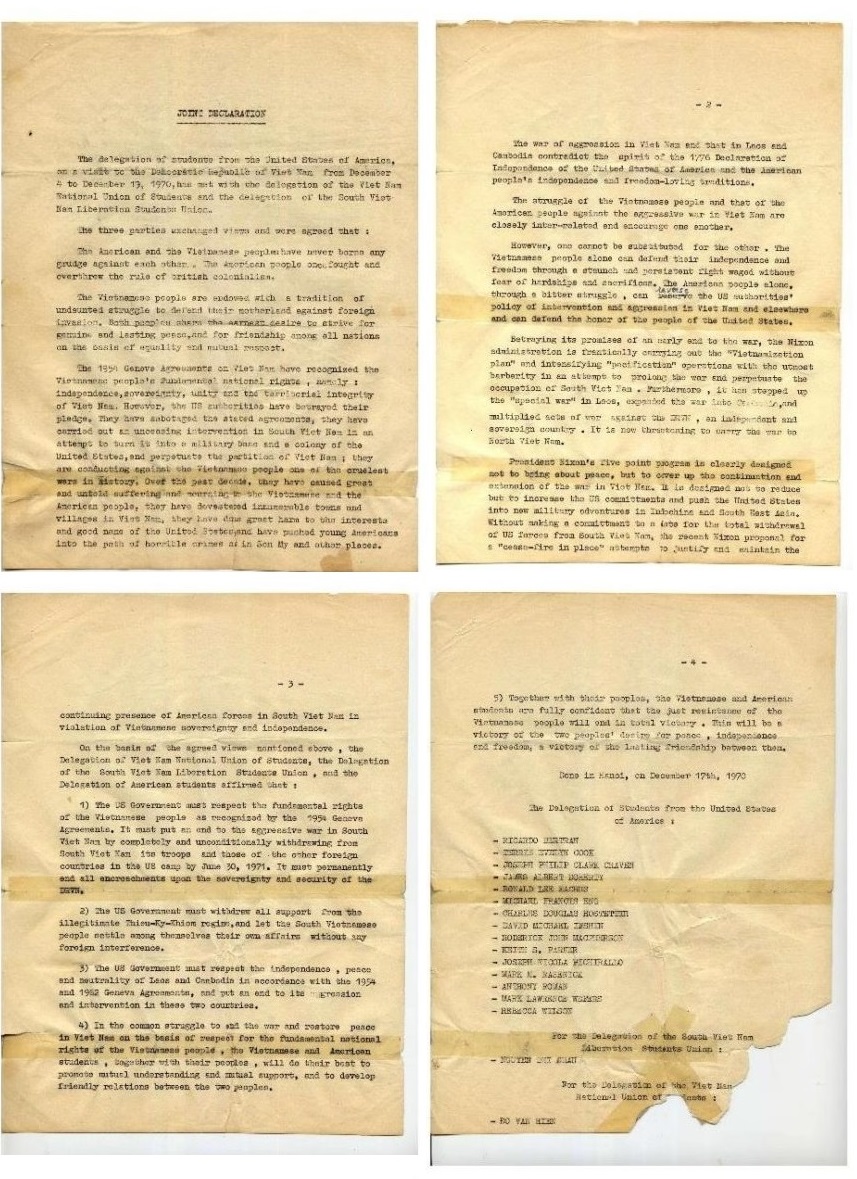

In December of that year, Ifshin led a delegation of American students who intended to go to both South and North Vietnam to meet with their counterparts from the South Vietnam National Student Union, the South Vietnam Liberation Student Union and the North Vietnam Student Union.

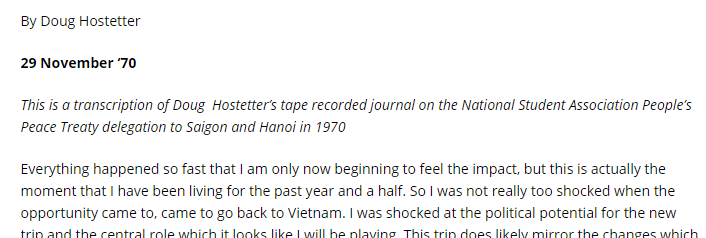

The intention was for the students to fly to Saigon and then on to Hanoi so that they could meet with counterparts from both parts of Vietnam. They were able to get visas from the North Vietnamese government, but the South Vietnamese government refused to issue visas. But, wrote delegate Doug Hostetter in an article published shortly after the trip, “Fortunately NSA neglected to place my name on the list of delegates circulated to embassies and the press, so I left for Vietnam a few days before the delegation’s scheduled departure, traveling on a tourist visa.” Click here for a transcript of Hostetter’s tape recorded notes on his trip to both South and North Vietnam.

The origins, signing and other details of the People’s Peace Treaty are documented in a pamphlet People’s Peace Treaty a Strategy for Ending the War from Irvine chapter of the New University Conference. That article called the treaty “an important document” that “breaks through the lies and distortions of the Nixon Administration and the U.S. press as to what is really going on in Vietnam.”

In Hostetter’s article I referenced earlier, he described the initial response to the PPT, which included endorsements “from 300 student body presidents and, impressively, among the thousands who have signed, we now have a West Point Cadet, the Mayor of Des Moines Iowa, an IRS auditor and a horse breeder! ” Hostetter also wrote a recent historical look back at the treaty for the Vietnam Peace Commemoration Committee.

Scroll down for the text of the treaty and other documents.

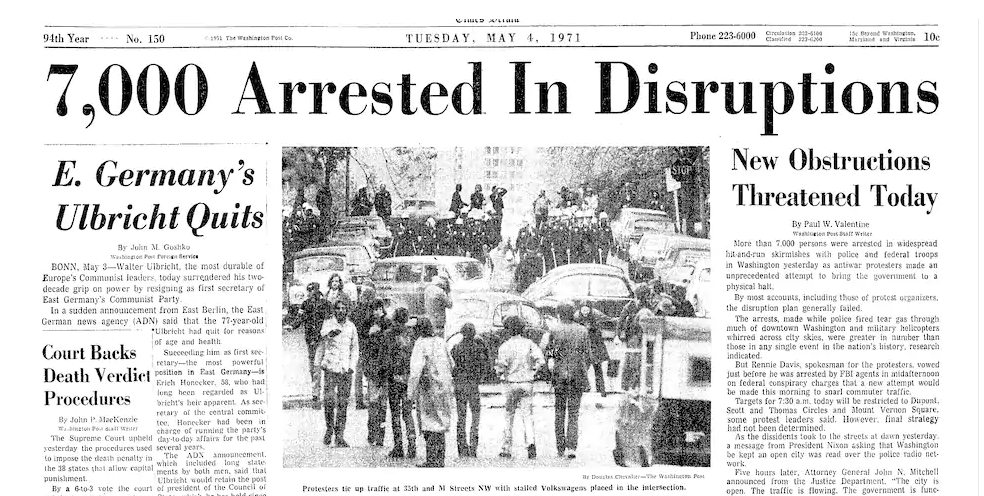

May Day Demonstrations

All of us who worked on the People’s Peace Treaty knew that the document, no matter how well received, would not end the war. For that we needed pressure on all fronts — in Congress, the United Nations and in the streets. To that end, the treaty helped lead to the May Day Demonstrations of May 1971 where 7,000 people were arrested in protest. That demonstration, historian and organizer L.A. Kauffman told the Washington Post ″contributed to helping end the Vietnam War and pioneered a new model of organizing that would shape movement after movement in the decades to come,” He added, “May Day 71 was a crucial turning point in our history.”

Official Paris Peace Negotiations

As I mentioned, there were discussions by myself, Rennie Davis and others with delegates from the Paris Peace Talks, including Madame Binh from the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam. As the newsreel video below illustrates, Binh had been talking with her counterparts from the U.S., North Vietnam and South Vietnam since 1968 — nearly three years before we drafted the PPT.

But, on January 3, 1973 — about two years after the signing of the PPT, the official government representatives finally did come to an agreement, though the war dragged on for a couple of years after the official agreement was signed.

As summarized by Britannica, it included an “immediate cease-fire, the withdrawal of all American military personnel, the release of all prisoners of war, and an international force to keep the peace. For their work on the accord.” Henry Kissinger, representing the U.S. and Le Duc Tho, representing North Vietnam, won the Nobel prize for “jointly having negotiated a cease fire in Vietnam in 1973.”

If the provisions of that official agreement sound familiar, they’re not all that different from the ones that the students agreed to years and tens of thousands of deaths earlier.

Thoughts from a half century later

The People’s Peace Treaty was one of many efforts by people around the world to end what we considered to be an unjust war. Of course not everyone agreed. A 2019 post by CBS News shows how Americans felt about the war over time. In 1965, only 24% of Americans though it was “a mistake” with 60% on the other side. By January, 1971 those numbers almost reversed themselves, with 60% agreeing it was a mistake and 32% thinking it wasn’t. By 1985 — more than a decade after the war was over — 72% of Americans said that the U.S. “should have stayed out,” but — interestingly, by 2018 that number shrank to 51% (though only 22% said the U.S. “did the right thing.” I haven’ seen any more recent polling but my sense is that most Americans and most American politicians from both major parties agree that the Vietnam war was a very costly and bloody mistake.

In 2018 I visited Hanoi and other parts of Vietnam and, had I not gone out of my way to visit commemorative museums, including the “Hanoi Hilton” where John McCain was imprisoned, I wouldn’t have seen much evidence that there had ever been such a war. And that’s certainly true here in the United States as well. But, as with all aspects of history, it’s important not to forget both the atrocities committed in our names and how millions of Americans stood up to protest that war and help bring it to an end.

I also want to say that while I will never fully forgive politicians and high-ranking officials who prosecuted that war, I have no animosity to the soldiers, sailors and air men who were sent to fight. Some were drafted, some enlisted and quite a few protested the war in their own right. But none of them were responsible for the policies the led us and kept us in Vietnam and I honor their services along with the men and women who now serve in the U.S. military.

But I also honor the peace makers then and now. One of the slogans during the antiwar movement was “Peace is Patriotic,” and that’s as true now as it was then.

The People’s Peace Treaty was one of my generation’s many efforts to bring about a better and more peaceful world. That work continues.

-end-

Watch a webinar about the People’s Peace Treaty from March, 2021 featuring

people who were instrumental in organizing, signing and promoting the treaty.

Documents and Background

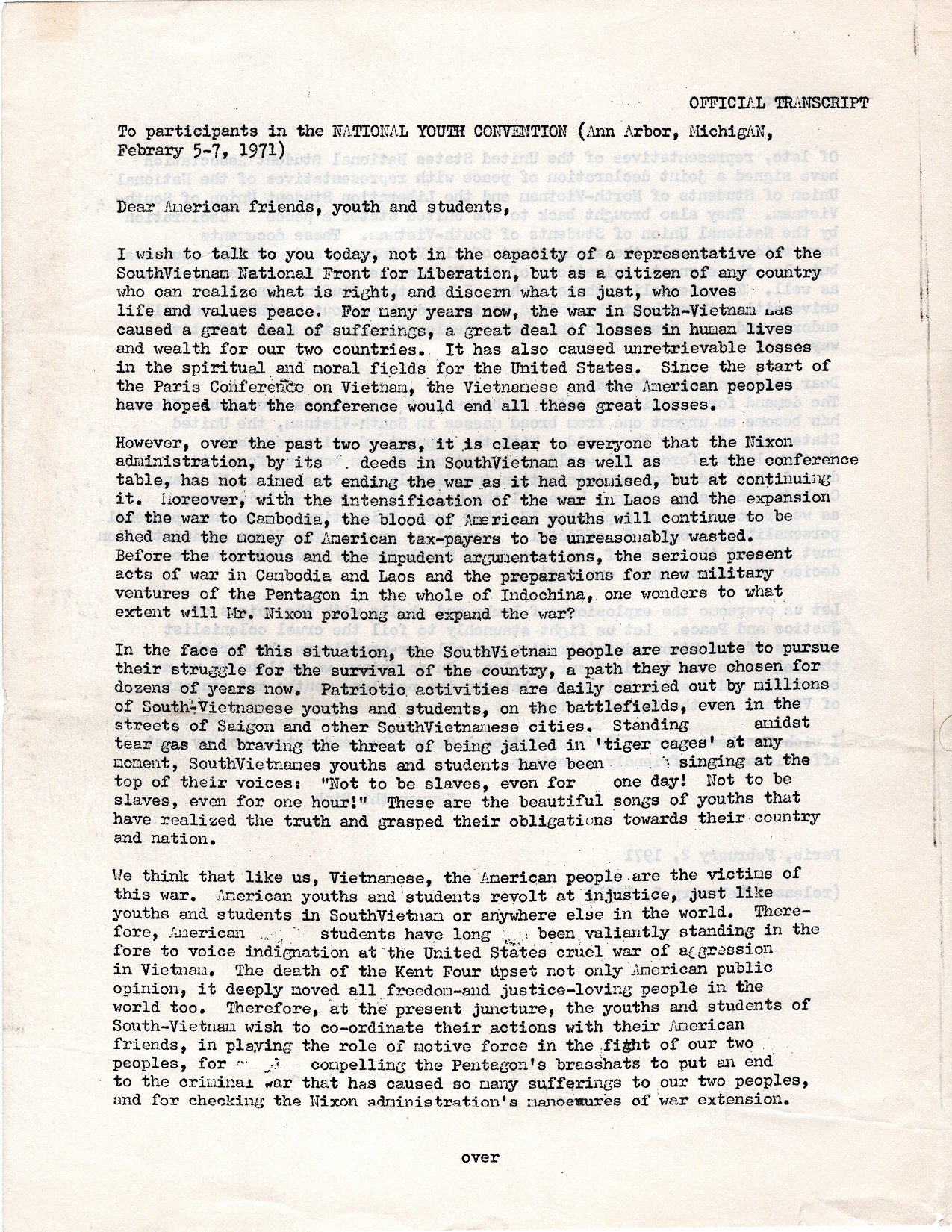

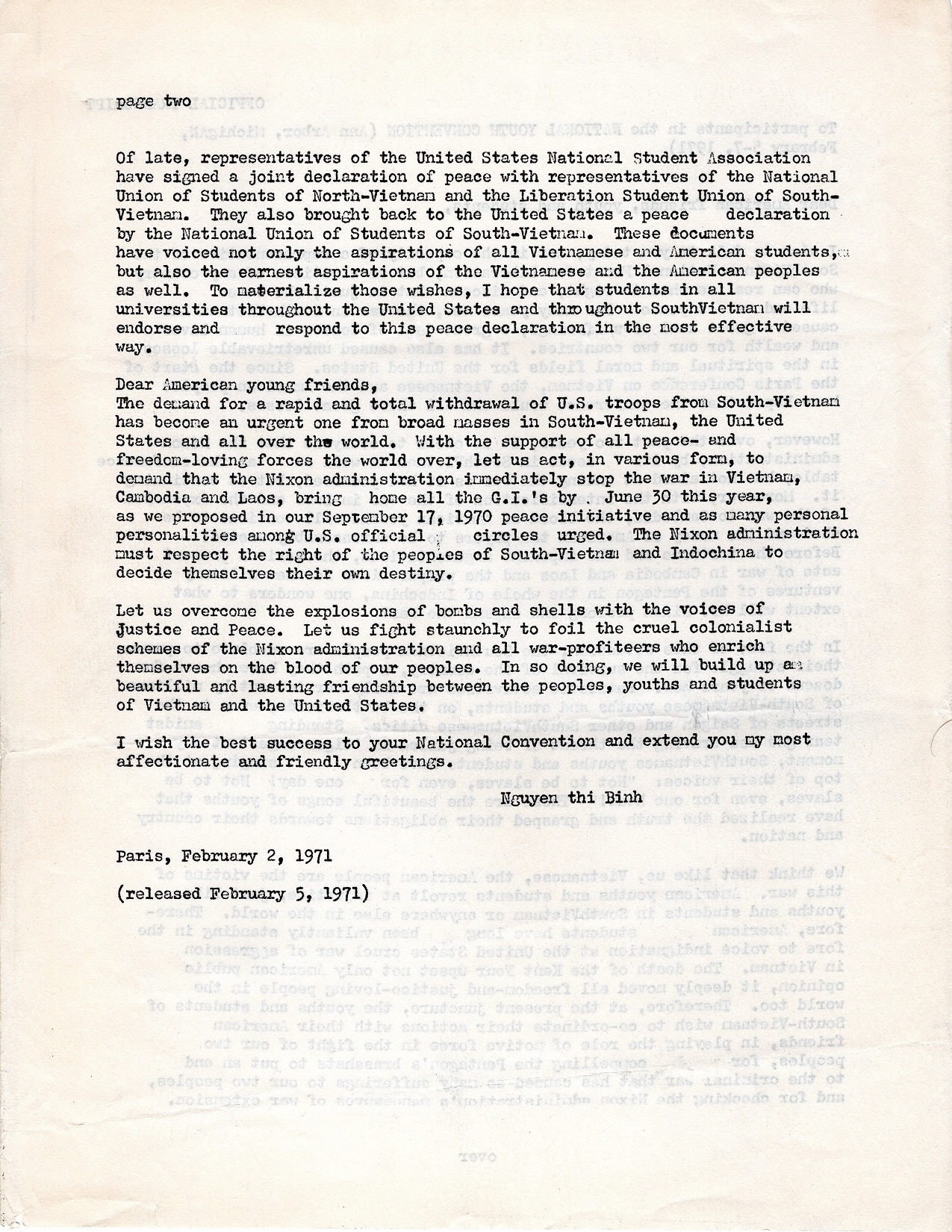

Letter from Madame Binh to National Youth Convention

State Department Summary of People’s Peace Treaty

People’s Peace Treaty Spring Action Project

People’s Peace Treaty history from Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars

Prelude to NSA’s support of People’s Peace Treaty

Newsreel footage on Paris Peace Accords

Original People’s Peace Treaty

Rennie Davis letter to Madame Bình

Nguyễn Thị Bình

Provisional Revolutionary government of South Vietnam

November 1, 1970

Dear Madame Binh,

I want to introduce you to my good friend Larry Magid. Larry is helping to organize a student delegation for a trip to Saigon and Hanoi this month. The delegation will be designed for maximum publicity to show support for the Saigon Student Union and the other opposition forces in South Vietnam.

When I was last in Paris, I discussed with you an idea of a citizen’s “peace treaty,” a kind of joint communique signed by Vietnamese and Americans outlining the correct steps for ending the war. The concept of a citizen’s peace treaty is gaining enormous support in the United States, especially with moderate and hard-to reach groups. Larry can explain the idea of the “treaty” in greater detail and our plans for ratifying the treaty throughout the United States.

I would appreciate any help you could give in suggesting individuals in Saigon who might meet with our American youth delegation and any assistance you could offer for ….. (that’s the end of page one — page two is missing”

Rennie Davis

Letter from Madame Binh to National Youth Convention

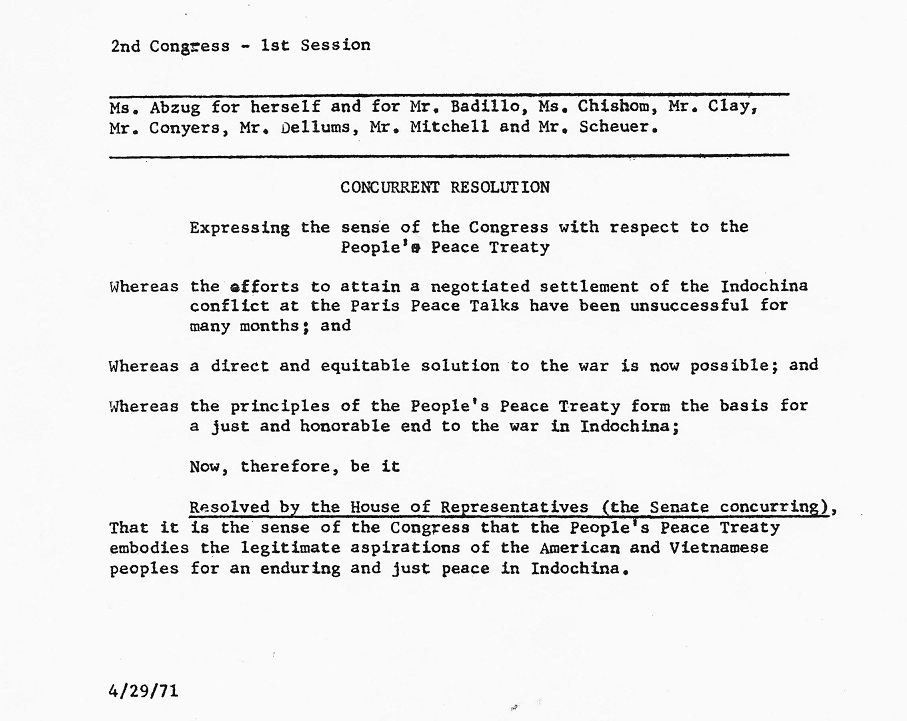

U.S. Congressional resolution

Doug Hostetter’s People’s Peace Treaty Vietnam Journal

The People’s Peace Treaty text

A Joint Treaty of Peace

BETWEEN THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES, SOUTH VIETNAM & NORTH VIETNAM

Be it known that the American and Vietnamese people are not enemies. The war is carried out in the names of the people of the United States and South Vietnam but without our consent. It destroys the land and people of Vietnam. It drains America of its resources, its youth and its honor.

We hereby agree to end the war on the following terms, so that both peoples can live under the joy of independence and can devote themselves to building a society based on human equality and respect for the earth. In rejecting the war we also reject all forms of racism and discrimination against people based on color, class, sex, national origin and ethnic grouping which forms the basis of the war policies, present and past, of the United States.

- The Americans agree to immediate and total withdrawal from Vietnam, and publicly to set the date by which all U.S. military forces will be removed.

- The Vietnamese pledge that as soon as the U.S. government publicly sets a date for total withdrawal, they will enter discussions to secure the release of all American prisoners, including pilots captured while bombing North Vietnam.

- There will be an immediate case-fire between U.S. forces and those led by the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam.

- They will enter discussions on the procedures to guarantee the safety of all withdrawing troops.

- The Americans pledge to end the imposition of Thieu, Ky and Khiem on the people of South Vietnam in order to insure their right to self-determination, and so that all political prisoners can be released.

- The Vietnamese pledge to form a provisional coalition government to organize democratic elections. All parties agree to respect the results of elections in which all South Vietnamese can participate freely without the presence of any foreign troops.

- The South Vietnamese pledge to enter discussion of procedures to guarantee the safety and political freedom of those South Vietnamese who have collaborated with the U.S. or with the U.S.-supported regime.

- The Americans and Vietnamese agree to respect the independence, peace and neutrality of Laos and Cambodia in accord with the 1954 and 1962 Geneva conventions, and not to interfere in the internal affairs of these two countries.

- Upon these points of agreement, we pledge to end the war and resolve all other questions in the spirit of self-determination and mutual respect for the independence and political freedom of the people of Vietnam and the United States.

By ratifying this agreement, we pledge to take whatever actions are appropriate to implement the terms of this Joint Treaty of Peace, and to insure its acceptance by the government of the United States.

South Vietnam National Student Union

South Vietnam Liberation Student Union

North Vietnam Student Union

National Student Association

Saigon, Hanoi and Paris, December 1970

Signed:

Adopted by New University Conference and Chicago Movement Meeting,

January 8-10, 1971

People’s Peace Treaty · 156 Fifth Ave., New York, N.Y. 10010 · (212) 924-2469